Curator of the exhibition : Philippe Régnier

In Les Métamorphoses, which he began writing in the year I, Ovid offers in book III a personal vision of the Greek myth of Narcissus: “Nearby there is a fountain whose pure, silvery water, unknown to the shepherds, had never been disturbed either by the goats grazing on the mountains or by the herds of the surrounding area. (…) There, tired of hunting and the heat of the day, Narcissus came and sat down, attracted by the beauty, the freshness, and the silence of these places. But while he quenches the thirst that devours him, he feels another thirst coming on, one that is even more devouring. Seduced by his image reflected in the wave, he becomes enamoured of his own beauty. He lends a body to the shadow he loves: he admires it, he remains motionless to its aspect, and such as one would take it for a marble statue of Paros. Leaning over the wave, he contemplates his eyes like two sparkling stars, his hair worthy of Apollo and Bacchus, his cheeks coloured with the brilliant flowers of youth, the ivory of his neck, the grace of his mouth, the roses and lilies of his complexion: he finally admires the beauty that makes him admire “.

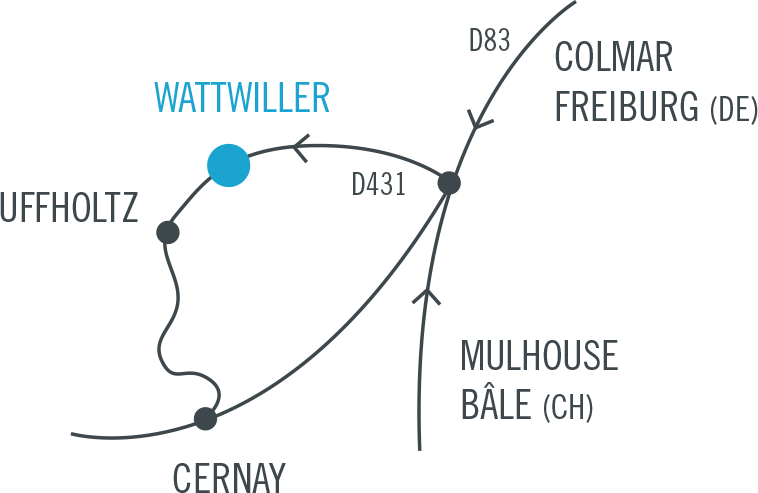

This myth of Narcissus very quickly inspired artists, as early as the Roman period, as shown by the works on this theme found in Pompeii. Numerous painters later took up this iconography, from the Fontainebleau school with the fresco by Nicolo Dell’Abbate based on the drawings of Primatice (Château de Fontainebleau), to Caravaggio (Galleria nazionale d’arte antiqua, Rome) and Poussin (Musée du Louvre, Paris). This extremely rich narrative deals first and foremost with the question of the image, the representation of the world, the very foundation of the visual arts. At the François Schneider Foundation in Wattwiller, an art centre dedicated to water, located near an important spring, the myth of Narcissus takes on its full meaning since it is the wave that becomes the source of the image, which sends back to its surface a double of the reality reflected in it. In his book De Pictura, the Renaissance painter and architect Leon Battista Alberti considers the myth of Narcissus to be the founder of painting: “I used to tell my friends that according to the poets, this Narcissus transformed into a flower had been the inventor of painting, and that, since painting is the flagship of all the arts, the whole story of Narcissus is perfectly suited to painting. Could you say, indeed, that the act of painting is something different from the act of artfully embracing the face of the water of this spring? »

A very classical representation of this iconography opens the exhibition, with a painting attributed to François Lemoyne, Narcissus contemplating his reflection in the water, dating from the 18th century and kept at the Dole Museum of Fine Arts. In this painting, the young man contemplates himself in a pond in front of an agitated landscape characteristic of the painting of this period. After this painting, heir to the history of art, the exhibition proposes a contemporary reading of the myth. Many artists have reflected on this question, directly or indirectly, including Bill Viola whose video The Reflecting Pool is projected in a room located near the painting attributed to Lemoyne. In this 7-minute work produced in 1977-79, a man comes out of the forest and approaches a pool. His reflection appears on the surface of the water. He then jumps, but as his body freezes above the wave, his image disappears little by little… Further on, the Japanese artist Yayoi Kusama has designed a special presentation for Wattwiller of his Narcissus Garden, a set of several hundred reflective spheres that will return the images of each visitor. Outside, on the terrace of the art centre, Dan Graham’s piece Two cubes, one rotated at 45° (1986) will allow the public to reflect in the glass walls, but also to glimpse nature and the sculpture garden of the François Schneider Foundation through transparency.

Beyond the reflection as such, the nature of the returned image is also central. Ovid poses the question of the seduction of Narcissus by his own reflection, of the confrontation with oneself, even if in the case of the myth, the fascination is extreme. Throughout the exhibition, each visitor will be able to confront his or her own image, face and person through the works of numerous artists. This will be the case with the mirror accompanied by the neon word “Ghost” by Claude Lévêque, Murmures (Ghost), 2013, or the faceted image reflected by the Mirror Mask (2013) by Kader Attia. Pistoletto will also invite us to question ourselves with his mirror-covered Tables of Judgment (1980). This last room will also include extremely poetic works, such as Marc Couturier’s Barque de Saône or Richard Baquié’s large installation Passion oubliée (1984). There will also be talk of appearances and disappearances, particularly Óscar Muñoz’s video in which a face traced in ink on water gradually disappears. Some artists also play with metaphor, summoning visitors’ imaginations, such as Lawrence Weiner, who will present a recontextualized work especially for the exhibition. The tour ends with Ann Veronica Janssens’ piece Cocktail sculpture, a glass aquarium filled with paraffin-coated water, in which it becomes impossible to see oneself…

The exhibition will also include works produced especially for the event by Franck Scurti, Maxime Rossi and Adel Abdessemed.